Why AIs in games are interesting (and useful)

Board games, have evoked a sense of excitement and thrill among players and audiences alike, especially when an interesting strategy is employed in the game, and it works - resulting in an extremely favorable situation or even a winning position. The more intricate the strategy, the greater the feeling of wonder and appreciation. Games like Chess and Go have an aesthetic component associated with them, for these very reasons. The social bonding (or not) that results from playing board games in tight friend and family circles is beyond the scope of this article. The focus here is more on the aspects that need to be considered by a player while making their decisions during a game. Strategies are very akin to real life decision making - where all aspects of a situation have to be understood and analyzed before making a decision. Often times it is necessary to consider not just the short term benefits of making a decision, but the possibilities that may arise from extrapolations of that decision into the future.

Board Game AIs evoke a similar sense of excitement - that of amazement and discovery - when these AI programs discover strategies from scratch, that have been discovered after lot of human thought. However the greatest feeling arises when an AI discovers strategies that were previously unknown to humans, thereby contributing to the human knowledge base and expanding it.

Commercial board games are different from age-old classics like Chess and Go. There is a large number of commercial board games and not all of them become popular. A popular board game has to excel in several aspects - artwork, theme, mechanics, play time and to an extent, level of difficulty. Keeping the other topics aside, here we only consider board game mechanics. If the mechanics are designed in a way that there is scope for over-powered (OP) strategies, the design is flawed. An OP strategy allows a player to very easily tilt the outcome of the game with little effort, and sometimes due to sheer luck (e.g., being handed an OP card for instance) thus ruining the competitive and equal opportunity assumptions at the start of the game. For this reason, extensive play testing of a game is extremely important before its release, to discover and completely iron out any such inconsistent strategies. This aspect is sometimes not paid enough attention to as it should - and thus unfortunately makes a splendid looking game, not so attractive to seasoned players.

Board game AIs can greatly accelerate play testing, by identifying OP mechanics using simulation of a large number of games. Monte Carlo Tree Search, or MCTS, is one such AI technique that is agnostic of the game mechanics and (theoretically) converges to the optimal play relying only on a large number of simulated outcomes.

Agricola - Farming in 17th century Europe

Agricola is a popular turn-based strategy board game by Uwe Rosenberg. The theme of the game is 17th century farming - where players take on the role of a farmer, who has to tile their lands, sow and harvest their crops, breed their farm animals, expand their family and build/renovate their homes with better material. For each of these activities there are action spaces on the board, which are succesively used by players in a turn based manner. Points are rewarded for improving each aspect of the farm (diversity is important!). The winner is the one who has scored the most points at the end of the game.

Agricola is also regarded as a very punishing game, as getting the action sequence for a particular set of actions (or even all of them) right, is very important. One missed opportunity or a blind spot here and there, and the results could be disastrous.

Over the years, Agricola has seen several expansions to the base game. These expansions introduced a whole new bunch of cards to the base set of cards (called Occupations and Minor Improvements) that enhance the gameplay with infinitely many new strategies arising from combining them in clever ways. Over time the community has identified a set of cards that are 'ban worthy', meaning that these cards can result in OP strategies and are therefore banned in any sort of competitive play.

My attempt in this project, was to implement the base version of the game. Implementing Occupations and Minor Improvement cards is going to be a mammoth task, and I might get to doing that sometime in the future. However, the purpose of this project was to demonstrate the capabilities of an AI algorithm in playing the game at a very decent (intermediate) level.

Monte-Carlo Tree Search (MCTS)

There are several techniques to evaluate the best move to play in a turn-based strategy (tbs) game. Minimax / Negamax is a well known technique to find best moves in a two player zero sum game, such as Chess. Alpha-Beta pruning is a technique used to prune the exponentially growing search tree in the Minimax algorithm. Though this is a very good technique, it often fails to explore certain branches that have a delayed reward - e.g., a sacrifice (bad initial move) that leads to checkmate (best final result) - and is very dependent on its evaluation function for a particular game state.

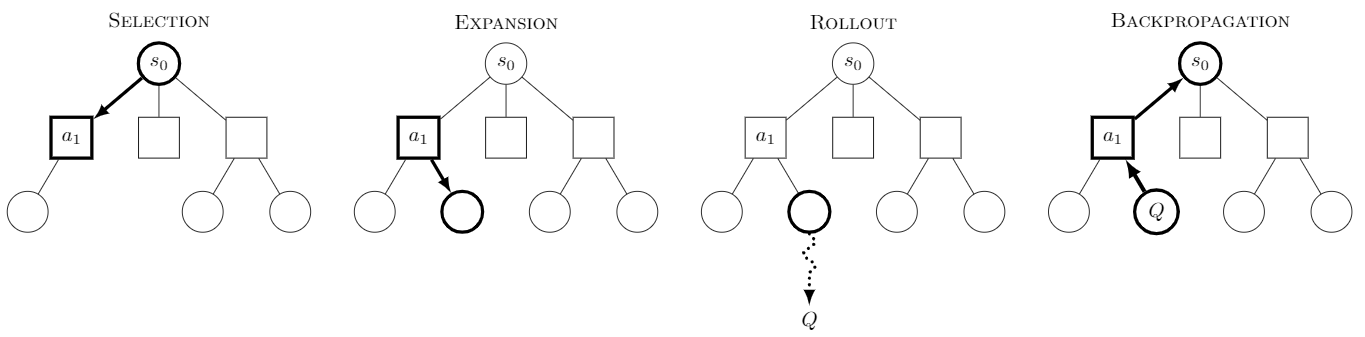

MCTS, on the other hand, makes no such assumptions. It is a purely knowledge-agnostic technique, which means that it requires no prior knowledge of how a game state is evaluated. It picks up on the best strategies as it searches through the game tree and is theoretically capable of perfect play given infinite resources. Hence its performance scales up with the number of searches it performs.

Agricola is a complex game with several actions within actions - known as split actions. MCTS is one of the few techniques that works with split action games as well.

Agricola is also an 'imperfect information' game, where certain information about the future board state as well as player hands (Occupation and Minor Improvement cards) are hidden from other players. While forward simulating playouts for such games from the perspective of player A, care must be taken to sample hidden actions from the entire hidden state space for all other players apart from A, rather than only from their own possible hidden actions. This ensures that player A does not 'learn' about the strategies that follow after other players play a hidden card from their hand, way before they actually play it.

In the current implementation, care is taken to not use a predetermined board state (knowing how the hidden board states will reveal themselves) but reveal hidden states during the simulated playouts - such that the AI does not 'learn' the best strategy by accessing a predetermined state (and thereby already knowing what's coming in the future).

Why Rust?

I chose Rust as my programming language for this project. Rust's incredible speed and memory safety coupled with several features akin to modern languages, instantly made me delve right into it. So far, dabbling with Rust for over a few weeks now, I have to say that it has emerged as one of my favorite languages to program in. Rust's ecosystem and community is one of the best out there, and frameworks such as the game engine Bevy, which uses Entity-Component-Systems (ECS) as its default paradigm, makes it especially attractive for projects that I usually like to work with.

In this project, the default Hash trait really came in handy. This trait implements a default hashing strategy for any kind of struct (provided all of its nested structs are also implementing the Hash trait) which allowed for easily implementing a game state cache that is needed by the MCTS algorithm.

Rust also encourages writing a lot of declarative style code (popularly referred to as idiomatic Rust) rather than imperative style code. This makes code more human readable and easier to reason about. In this project however, I am certain that a large number of improvements can be made in terms of writing certains pieces in a declarative style.

If you're interested in the project, you can find the source code here.

Observations and Learnings

Upon letting the AI agents battle themselves out, as well as playing the agents myself (as an intermediate player) I observed some key strategies. Given that my implementation isn't perfect - I encoded some sub actions to be locally handled as I did not want the search tree to become unmanageable - the AI agents learned an optimal strategy around it. In a 2p game, the AI agents consistently scored about 45-50 points and in a 4p game, they scored about 30-40 points - which are relatively good scores considering that they were only allowed an MCTS cache size (game states that the search tree would be expanded to) of 20,000 game states per move. The AI however did not see deep enough to understand the well-known human strategy of trying to grow the family first so that the cumulative number of actions could be maximized. However, it prioritized farming and fencing a lot, and often ended up with complete pastures with sizeable animal populations alongwith a large number of fields. It did not prioritize building rooms as much as normal human players, but still ended up with good scores with a small family size. The AI also prioritized stacking a lot of food in the initial game just to make sure that they didn't have to take begging tokens. Since the base game has limited sources of food, this seemed like a reasonable strategy. In the future, interesting experiments would entail increasing the cache size to see if the AI can indeed discover these deep human strategies.